By Aileen Macalintal

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

First of Two Parts

Mina, a 26-year-old government employee from Bicol, deactivated her Facebook account and changed her phone number early in 2022 after an online lending app (OLA) revealed her debt in public.

The app accessed her phone contacts and texted them. Her relatives and acquaintances received the message.

Mina fell victim to online lending apps now infamous for data privacy breaches, intimidation, harassment, and unfair debt collection practices. In other countries, lending apps have been linked to depression, trauma, and even suicides.

Digital loan sharks are preying on borrowers in this perfect storm of pandemic, social isolation, soaring inflation and unemployment, and light-touch government regulation on the fintech boom.

Mina borrowed from as many as 20 OLAs when her pockets went empty and she had no one to turn to. During the pandemic, she waited months for a contractual job offer.

Her debts ballooned to almost six figures because she kept on borrowing to repay high-interest debts, a practice called “tapal,” the Filipino word for a patch-up or stop-gap measure. She continued borrowing money even after securing a job because salary delays stretched to three weeks.

On the day she was publicly shamed, work was up to her neck. But she had cash to spare.

“Alam ko due date that time. Kaso busy talaga ako that day sa work. ‘Yung phone ko nagcha-charge. May pambayad ako noon, pero sabi ko mamaya na lang kasi ang dami kong ginagawa. Tumatawag na pala sila, hindi ko napansin. Mag-12 o’clock na tapos sabi bigla ng officemate ko, ano ito, Mina? Pinakita niya ‘yung text sa akin, ‘may utang ka raw sa online lending at magbayad ka daw.’”

(I know that payment fell due at that time. But I was busy at work. My phone was charging. I had money to pay for it, but I said I’d do it later because I had to finish work. They were calling and I didn’t notice it. It was nearly 12 noon when my officemate asked me, “What’s this, Mina?” She showed me a text message that said I owned money to an online lending app.)

Mina wanted to vanish from the face of the earth.

One by one, her officemates approached her to confirm the texts. She remained composed and feigned ignorance. When she arrived home, she burst into tears, alone. She sobbed all night.

“Ang bigat ng dibdib ko (my chest was heavy),” she said. “I’ve done something so bad.”

She felt sorry for herself. How could she explain to her family and friends that she owed several digital apps nearly P100,000? How could she repay the loans with a meager salary from a contractual job?

Cash for food, boarding house, and other daily needs

When Mina told everything to her sister in Japan, the bewildered overseas worker asked what she used the money for.

“Did you buy a motorcycle?” her sister asked. In the Philippines, commuters have turned to motorcycles to deal with the lack of public transportation and the traffic gridlock.

Mina said she needed cash to buy food, pay for her boarding house, and meet her daily needs while waiting for her employment papers. Burdened with family and financial problems during the pandemic, she turned to the easy-to-download lending apps.

“Iyak talaga ako nang iyak. Tapos rosary. Tipong hindi ko na alam gagawin ko. Hindi na ako nakakakain noon. Tapos inamin ko sa group chat sa office, ‘sorry guys, I lied, ayoko lang mag-cause ng scene sa office kasi the more na mag-comfort kayo, the more na hindi ako magiging okay,’” she said.

(I kept on crying and praying the rosary. I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t eat. I admitted to the office group chat, “Sorry guys, I lied. I didn’t want to cause a scene in the office. The more you comforted me, the more I didn’t feel okay.”)

Mina settled all her debts. Her sister gave her money. She also sold her laptop and couch. But the harassment continued.

She finally called the OLA, SunCash, and demanded answers. “Why did you notify my contacts?” They hung up on her. Then they blocked her.

“I contacted them the whole afternoon. I gave them the reference number. I told them I was going to pay but they couldn’t wait. The text messages went away but my officemates were concerned,” she said.

Public shaming pushed Mina to leave her Facebook friends and hide behind a dummy account. She searched about OLAs and found Facebook groups of victims. She realized she was not alone. In fact, others had worse experiences.

“Nag-Google ako ng iba pang victims. Wow, grabe, ang dami pala. Naliwanagan ako na grabe ‘yung experience ng iba. Kasi ‘yung pag-text pa lang sa contacts ko, na-trauma na ako du’n e. ‘Yung iba may death threats pa, tipong ‘Papatayin kita! Pupugutan kita!’” said Mina.

(I googled about other victims. Wow, there’s a lot of them. I learned that they went through a lot. When I texted my contacts, I was traumatized. But others got death threats. They were told, “I’ll kill you! I’ll cut your head off.”)

She also saw Facebook group members mentioning suicide. Financial strain, rooted in financial debt or crisis, unemployment, past homelessness, and lower incomes, have been linked to higher risk of suicide attempts.

Death, rape threats

Thirty-six-year-old Chel of Taguig is also a member of OLA groups on Facebook.

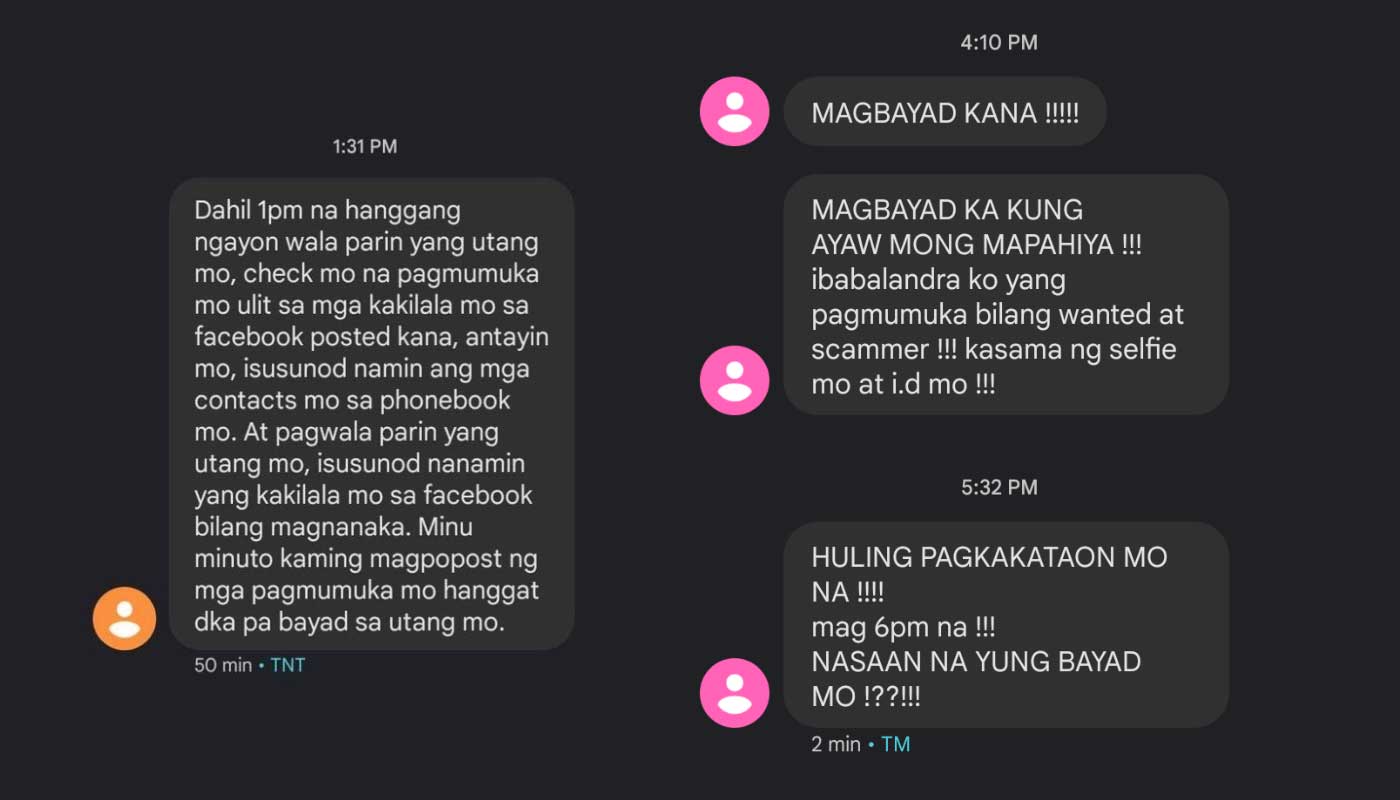

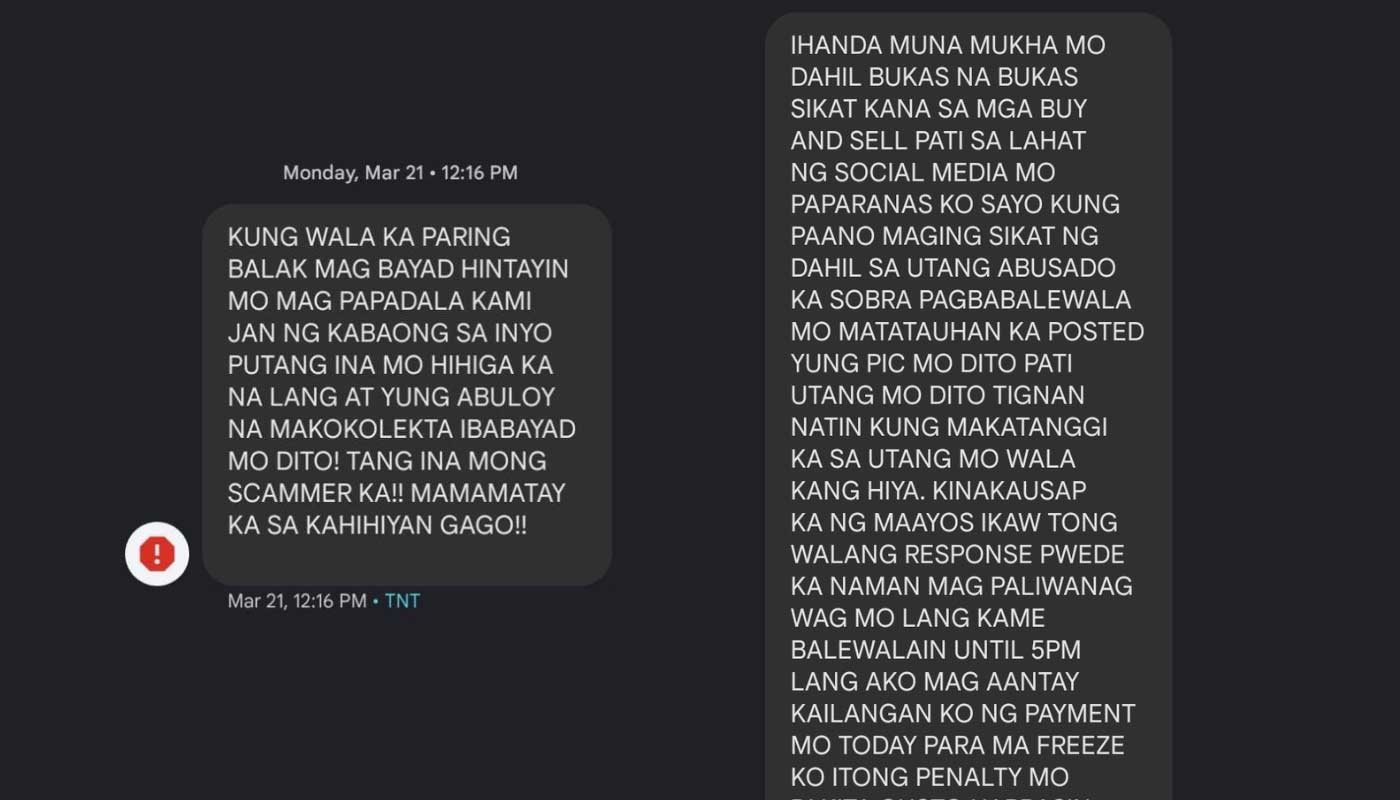

Chel received curses, insults, and even threats of rape and death when in March 2022, she missed a payment to the “Kuya Loan” app that lent her P3,500. The unemployed mother of five forwarded to the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) some of the texts in all caps:

“Nag-text din sila sa asawa ko, sabi po nila, ‘kami po ay nakikiramay sa pagkamatay ni (Chel’s full name). Kaya po magpapadala kami ng kandila, bulaklak, pa-kape. Bago po siya namatay, kanya pong hinabilin na kayo daw po ang magbabayad sa kanyang naiwang utang sa aming kumpanya.’ Tama po ba yun?”

(They texted my husband. They said, “We condole with you on the death of [Chel’s full name]. We will send candles, flowers, and coffee. Before she died, she told us that you will pay for the debts she owed to our company. Is that correct?”)

“Pati pala kapitbahay ko na naka-save sa phonebook [nadamay]. Pinuntahan ako ng kapitbahay ko, pati raw sila kung anu-ano pinagte-text. Hindi na maganda, kaya pina-print ko ‘yung mga text.”

(Even my neighbor who’s saved in my phonebook got dragged into my problem. My neighbor told me about the text messages they received. It didn’t look good. I had these text messages printed out.)

The OLA also created a Facebook group chat, added Chel’s friends, and blasted the message that she was a “scammer” and an “estapadora” (swindler).

Chel reported the Kuya Loan app, operating under Ward Lending Corp., to the barangay or village authorities. “Pina-blotter ko lahat ng text nila (I had their text messages put in the blotter),” she said.

“Sabi ko sa GC, ‘Hindi ako tatalikod sa utang ko. Babayaran ko ‘yan. Pero ang gusto kong mangyari, dito tayo sa barangay magkabayaran kasi ‘yan ang advice ng barangay.’ Sabi ko pwede ko silang kasuhan ng libel o cybercrime, sabi ng mga abogado na hiningian ko ng tulong. Nag-leave sila sa GC,” she said.

(I told the OLA in the group chat, “I will not run away from my debts. I’ll repay them.” But I wanted to do the transaction here in the village office because that was the advice given to me by the village officials. I told them, I can file a complaint against them for libel or cybercrime. That was the advice given by the lawyers I talked to. They left the group chat.)

“Sa halagang ganoon, kailangan mong magbanta ng buhay ng tao?” Chel said. “Talagang na-stress ako.”

(For that small amount, they had to threaten someone’s life? I was stressed out.)

Reached by email, a Kuya Loan representative declined PCIJ’s request for an interview.

Regulators stretched

Complaints against OLAs or online lending platforms rose in recent years, according to the National Privacy Commission (NPC), the Securities and Exchange Commission, and other government agencies.

This problem is “unprecedented,” according to lawyer Michael Santos, chief of the NPC Complaints and Investigation Division.

The NPC was swamped with complaints of privacy breaches from all over the Philippines, particularly those involving depression, suicide, and miscarriage.

“We think that the phone contacts and the personal information of the borrowers were being weaponized to coerce the borrower,” said Santos. “We received complaints as far as Mindanao.”

However, the NPC is stretched.

“It took us several additional personnel to cope with this problem. For the past two years, our division has been the largest in terms of manpower. But you can only do so much in a timely manner without sacrificing due process. We have limited time in serving court orders,” Santos said.

“We are also limited by the budget given to us by Congress. We can only wish that we have all the high-tech gadgets and training … It’s a continuing process for us to know the intricacies of the online lending phenomena,” he said.

When the NPC fast-tracked its investigation in 2020, the number of complaints declined. The commission increased its 30-member complaints team to 50 and streamlined the process for filing complaints. In 2021, the complaints went down further to “a few hundreds.”

But many Filipinos, like Mina, don’t file complaints on harassment or privacy breaches as they don’t know how to report. They’re unsure if any real action will be taken, Mina said.

Santos said it was difficult to look for these lending outfits. “There’s the challenge of finding the offices of these companies especially during the pandemic when they closed their offices but continued to operate,” he said.

Santos said the accessibility of collateral-free microloans became an opportunity for abuses and harassment.

“Microloans are so accessible, you don’t have to go to a physical store. All you need to do is download and click on your phone,” he said.

Some loans are in fact auto-approved.

“‘Yung auto-approved loans, click mo lang ‘yung link tapos maya-maya may tatawag na, sasabihin okay na (You just click the link then someone calls you to say your loan was approved),” said 26-year-old Mina.

Victorio Dimagiba, a former trade and industry undersecretary who is now president of a consumer advocacy group, said the OLA problem was like an investment scam.

The government itself seems unprepared, Dimagiba said. “They don’t even know how to approach the problem,” he said. END

Illustration by Joseph Luigi Almuena