By Martin Genodepa

Of late, Ilonggo women have emerged from the shadows and have begun to take their rightful place among men in the male-dominated arena of art.

The growing visibility of women artists signifies that women, at large, have indeed turned assertive in finding expression for themselves, fortifying the collective struggle towards self-realization, and leveling the playing field for all genders. Female artists are now taking the proverbial bull by the horns to ensure that, also in art, women have the same chances available to men.

Ilonggo women have evolved from being a lin-ay (muse) to becoming a hangaway (warrior) in various fields and for diverse causes. They have ceased from merely being founts of inspiration and have emerged dauntless protagonists by blazing trails for themselves as well as for others.

Madhu Liebscher (b. 1964) started to do art in the 1980s. She may be considered as the only active female artist of Iloilo in that decade aside from the veteran ceramist Nelfa Querubin, who by then, had left for the United States. Her early paintings exhibited angst that were redolent of feminist assertions. She left Iloilo and returned fairly recently and has focused her creative energies in fabric art. Her soft sculpture made primarily of flour sack (katsa), scrap textiles and threads, titled Kasing Kasing ni Madhu, exemplifies creative upcycling even as it reiterates the challenge of putting more value to beauty of the heart than to physical beauty.

Adhara Sebuado (b. 1986) is a nurse by profession and a lactation consultant. In high school, she majored in Visual Arts in the Iloilo National High School Special Program for the Arts. As Sebuado transitioned into motherhood, her works center on maternity and breastfeeding, which are manifestations of her advocacy. Her mixed media work Langkoy is an indictment against women who do not observe family planning. The title is actually a local term for the successive giving of birth by lactating mothers. The circular format of an assembly of young children of various ages framing a life size pregnant torso covered with reproductions of certificates of live birth and topped with plaster of paris casts of feet of newborn babies suggests a cycle of gloom resulting from an unplanned family, disadvantaging women especially.

Pam Reyes (b. 1965) who has been in the personal accessories business before she turned to painting shows her adeptness at transforming photographs into paintings. What Does Our Future Hold? expresses anxiety that any caring adult would feel upon looking at children living in the squalor of the slums. The carefree pretty girl in the painting playing in the flooded narrow alley is both a sad statement about resignation to one’s circumstances and an exclamation of concern for the young, the proverbial hope of the land.

In State of the Nation, Bea Gison (b. 1996) views the country as one run by a ghoulish figure. In Prejudice she harnesses art nouveau to reference the biblical story of the fall of humankind in the Garden of Eden. Decking the woman with a garland of fruits that look like apples (popularly thought as the fruit eaten by Eve) Gison protests that the full weight of the blame for sin and its consequences landed on the female kind despite being, in truth, virtuous as indicated by the halo. The prejudice against women is intoned by the crucifixion marks on the hands of the subject, alluding to the wrongful suffering of Jesus Christ. The snake on the woman’s arm which, in the Bible story, represents Satan appears to have become the woman’s defender– its menacing stance and spiteful gaze provide a stark contrast to the woman’s steady but coy gaze. Maybe her being a Physical Therapy major, Gison exhibits mastery of the human form (and figuration, in general) in her paintings that are carefully crafted symbolisms of her political views.

Charmaine Española (b. 1977), a creative director in a business process outsourcing company, bares with steely courage her heart and soul in her paintings about her own womanhood. In the stylized portraits, My Truth Unfolds (Triptych) and Torn No More, Española admits her brokenness while proclaiming her healing at the same time. These monochromatic paintings are, therefore, expressions of tenacity, triumph, and hope. In My Precious Truth the artist simplifies what her essence is. Representing herself as a delicate lily, without subverting her femininity, she is asserting that she is resolute.

Closely related to woman-as-flower symbolism is The Journey of Life: Not I, But Who Is Within Me by Althea Villanueva (b. 1993). The heavily textured painting is a metaphor of woman as landscape. The depiction of a meandering road littered with flowers is a clever reminder of a woman’s reproductive power as it brings to mind the fallopian tube and female genitalia. It must be noted though that Villanueva who graduated from Central Philippine University with the degree in Tourism is also an active member of her church and the painting, from title, is her testimony of her own resilience as a spiritual woman. A surreal landscape, generally flourishing but drab even if a river runs through it, is a very creative declaration of such!

In collaboration with 80 persons – women – deprived of liberty (PDL), Ma Rosalie Zerrudo (b. 1970) was able to realize the installation FUERTElity Bilat Series (2019-2021). An artist-teacher and cultural worker, Zerrudo worked with communities and groups aiming to apply the idea of creativity as therapy – a means to shake off oppressive conditions and contexts. The installation deifies the woman as the fount of fertility and creative re-production. Various interpretations of the female external reproductive organ handcrafted using fabrics and threads by these women inmates cover the central figure, a metal female silhouette. The metal sculptures that are also shaped like vaginas on each side of the female form are also decorated with these. The installation looks like some primeval altar with the two sculptures serving as ramilletes de flores that adorn the altars of Catholic churches.

Margaux Blas (b. 1990) majored in Fashion Design and Merchandising, graduating with honors, from the De La Salle College of Saint Benilde, School of Arts and Design. Her works Baby Armalite and Good Luck Charm ni Manay are semi-autobiographical yet infused with wit and fun. In the former, Blas reveals her attitude towards her childhood; in the later, towards her adulthood. In the former, nostalgia with the representation of a blonde doll and cut-out paper doll dresses is mixed with some tinge of bewilderment at the type of playthings young Filipino girls like her were made to play. Her reworked portrait as a child may be the artist’s wish to change an aspect of her childhood into something less typical. In the latter, woman power is celebrated. In the scene reminiscent of Gauguin, albeit employing more refined and decisive strokes, the woman holding a cigarette with a snake (Blas’ pet) hovering around is a visual replay of ancient stories about some seductress waiting for a prey.

Lullabies in Prison and Sin-o si Mel Carreon? by multimedia and multi-awarded artist Mia Reyes (b. 1980) are strong social commentaries. Reyes was a grantee of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) for a Story Project in 2018 for Lullabies in Prison that documents the hapless conditions of the jail for women and shows how art has mitigated or dulled their psychic pains. Sino si Mel Carreon? attempts to provide an understanding of the persona of the perennial local candidate by following him as he campaigns for the nth time. People in the streets speak of their perceptions of Carreon; the subject also talks about himself stoking pathos instead of derision. In both videos, Reyes does not impose on the audience her readings of her subjects or their circumstances; this technique of simply supplying available information to the viewer makes her short documentaries mentally engaging.

Katelyn Miñoso (b. 2000) is currently completing her Communication degree major in Advertising and Public Relations. She won the Minor Prize Award in Legacy in the 2021 National Quincentennial Art Competition. Miñoso’s photographs of nature, people and events are the bases of her paintings. The artist has shown that she is comfortable with both abstract and figurative painting. Rubber Soul, The Click, Beach House and Bashful Creatures are paintings that play on color and texture; they document the fluctuations in the artist’s moods while revealing, at the same time, the breadth of her creative inspirations. In Lima, Miñoso proves that she is also at home with figurative painting. Her subject here is a well-known drifter in the city. Rendered in a mix of impressionist and fauvist styles, he is portrayed as a sentient being.

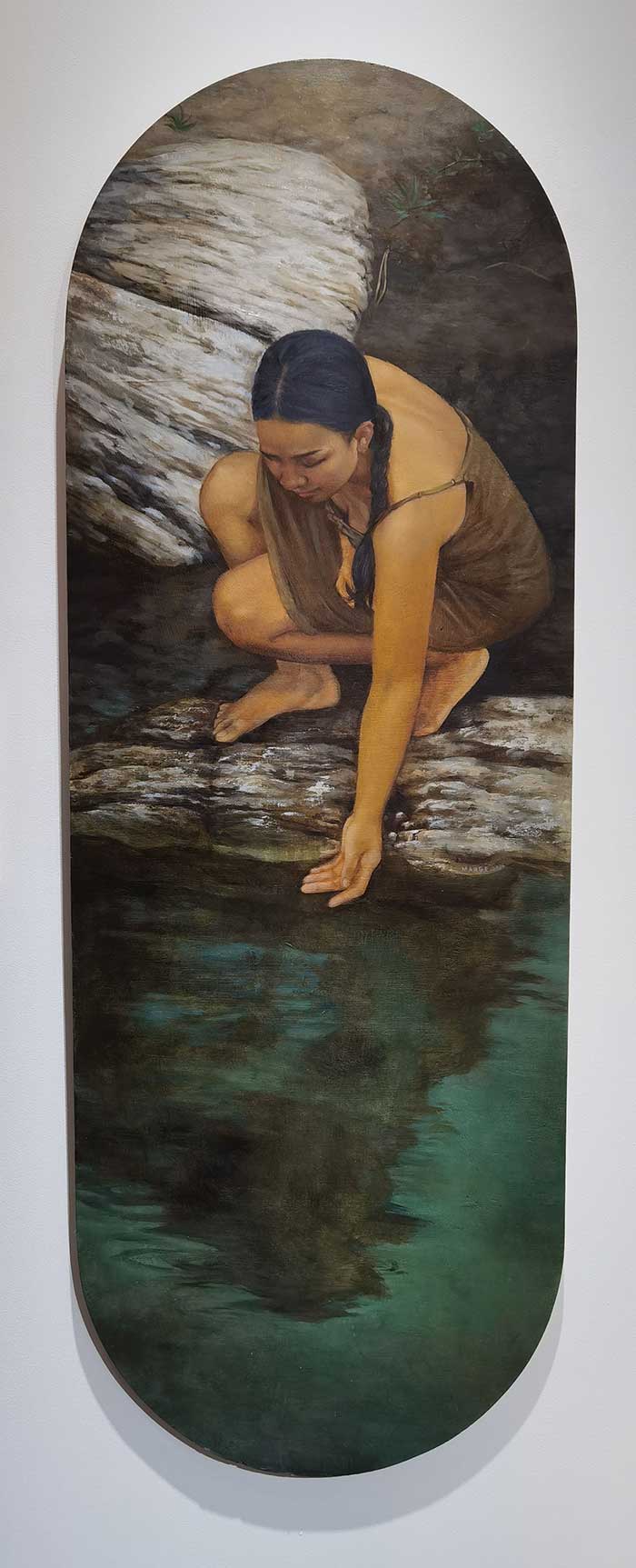

Ma. Margarita Aurora “Marge” Chavez (b. 1991) is one of the few Ilonggo artists who have academic credentials in art. She finished her Bachelor of Fine Arts major in Painting at the University of Santo Tomas, where she was the recipient of the Thesis of the Year Award. She was also a recipient of the Raghurajpur International Arts/Culture Exchange (RIA/CE) grant. The way Chavez renders her human figures either in pencil or oil could only be result of her inherent talent honed by discipline and enhanced by techniques she learned at school. Her untitled female nude drawings are delicate and lyrical and can stir a discussion on the female gaze. Lyricism and poetry, too, characterize her oil on wood painting Contemplation – a woman reaching out to her unclear reflection in the water is a well-crafted reiteration of the existential dilemma from a woman’s point of view.

Sheila Molato (b. 1986) has a degree in the medical field and has worked locally and abroad for several years. She started as a photographer for a European-run studio. Since then, she has participated in over 20 group exhibitions in Iloilo and Manila. Molato’s professional background surfaces when one considers the titles of her abstract works: The Cocoon Stage of Healing, Flexible Nervous System. They also intimate her motivations that inform her art production. With black being the dominant color, the forms and shapes that fill her canvases as at once tensile, terse and tentative intoning either a bleak present or a dreary prognosis.

Self-definition and self-actualization summarize the paintings of Shasha Cabais (b. 1994). Cabais was first inspired to engage in art upon seeing the artworks in the gallery where her father works in. She did portraits during her college years. Her skill at figuration manifests in Superficial Addiction and To Be Like You which are generally about discontent and desiring to be somebody else. But in Self Love and in Rebirth, Cabais, exhibiting consistency in skill in figurative painting, sees to be suggesting about contentment and acceptance of one’s self. Such acceptance is rooted in the anticipation of metamorphosis or positive change as symbolized by the butterfly.

Ilonggos can now revel in the reality that local women have stepped forward to be recognized for their creative powers. More importantly, they can take pride in the fact that the local women artists are not about to shirk from the challenges of the times or their circumstances – that they, too, can muster strength to control their personal lot and actively shape the destiny of everyone around them.

Through the self-referencing, perceptive, reflexive, impassioned, or even risqué works of these thirteen artists in the exhibit From Lin-ay to Hangaway, the voices of Ilonggo women that speak of their identities, knowledge, and strengths are heard – sundry but distinct.

———

From Lin-ay to Hangaway: Voices of Ilonggo Women Artists is on view at Lantip Changing Exhibition Gallery 2, Main Building, UP Visayas, Iloilo City until 31 July 2022. Gallery hours Monday through Friday 8:30a.m.- 4:30p.m.